How My Identity Influences My Activism

WORDS: GLORIA KIMBULU | ART: LOVEIS WISE

"Where are you from?” I respond, “Do you want the short answer or the long answer?”

The short answer is Nebraska where I have lived for most of my life. The long answer is, “Well, I am from the Democratic Republic of Congo but I was born in Spain and I moved to the United States when I was six years old.” As there has never been one specific place for me to call home, I’ve always had identity issues and trouble finding spaces for me to feel like I belong. Although I still grapple with my complex identity as a Spanish-born black Congolese woman living in the United States, in the past few years I have noticed that my identity has immensely influenced my activism and passion for social justice. Even though I only lived in Spain until I was six years old, I speak Spanish fluently and feel ties to Spanish culture. I have distant memories of my mother watching Maria del Barrio among other telenovelas and now I watch telenovelas all the time on Netflix. When we moved to the United States my parents would play Spanish cassettes in the car so now that I’m older, listening to singers like Chayanne, Elvis Crespo, Thalia and Azucar Morena on Spotify make me nostalgic. I often find myself laughing at Spanish memes I see on Twitter and Facebook and have realized that while I didn’t live in Spain for very long, I am still influenced by my time there.

I’m thankful I was able to learn Spanish in Spain because as Spanish is the second most-spoken language in the United States, I know my language skills are very useful here. I took Spanish classes from middle school through college and graduated with a minor in Spanish. During an immigration centered social justice internship, I had three summers ago, I translated blog posts from English to Spanish as well as spoke Spanish during events where a large portion of the audience members were Spanish speakers.

Even though I only lived in Spain until I was six years old, I speak Spanish fluently and feel ties to Spanish culture. I have distant memories of my mother watching Maria del Barrio among other telenovelas and now I watch telenovelas all the time on Netflix. When we moved to the United States my parents would play Spanish cassettes in the car so now that I’m older, listening to singers like Chayanne, Elvis Crespo, Thalia and Azucar Morena on Spotify make me nostalgic. I often find myself laughing at Spanish memes I see on Twitter and Facebook and have realized that while I didn’t live in Spain for very long, I am still influenced by my time there.

I’m thankful I was able to learn Spanish in Spain because as Spanish is the second most-spoken language in the United States, I know my language skills are very useful here. I took Spanish classes from middle school through college and graduated with a minor in Spanish. During an immigration centered social justice internship, I had three summers ago, I translated blog posts from English to Spanish as well as spoke Spanish during events where a large portion of the audience members were Spanish speakers.

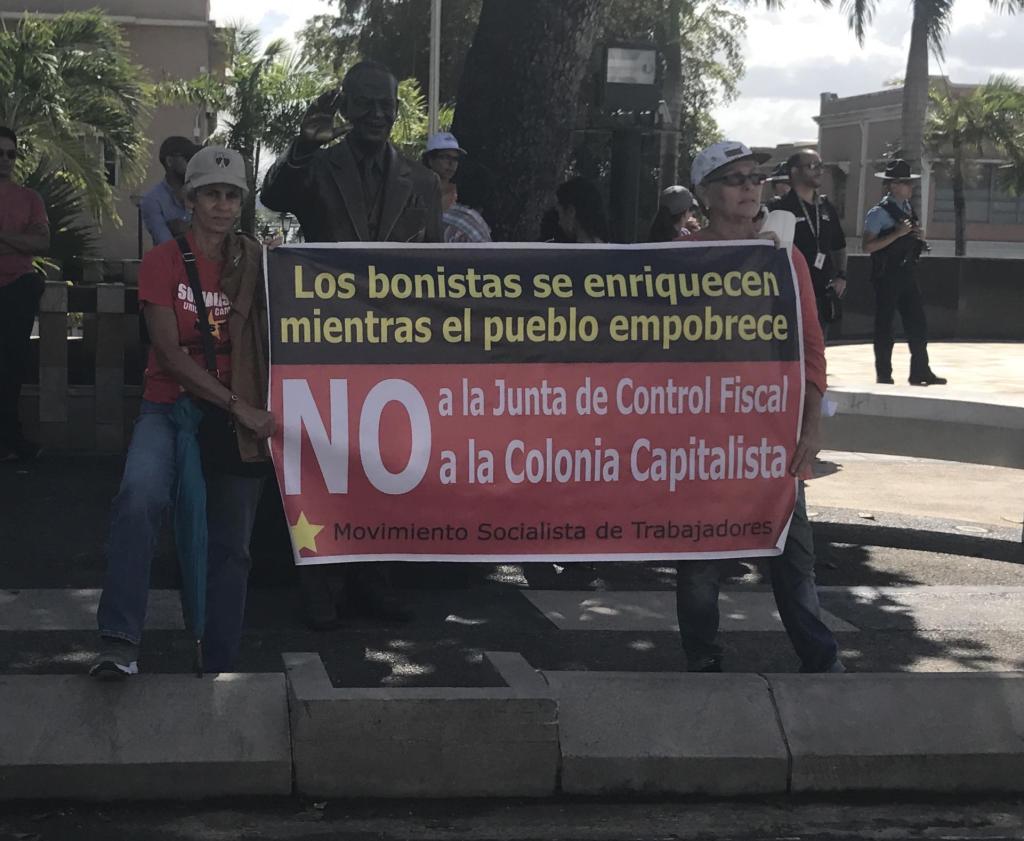

This past January, I traveled to Puerto Rico and spoke Spanish for most of the time that I was there. I attended a protest at the San Juan capitol building and knowing Spanish really helped me understand the purpose of the protests and the sentiments of Puerto Rican attendees. During this protest, Puerto Rican citizens were protesting for workers’ rights and an end to the exploitation of Puerto Rican people.

This past January, I traveled to Puerto Rico and spoke Spanish for most of the time that I was there. I attended a protest at the San Juan capitol building and knowing Spanish really helped me understand the purpose of the protests and the sentiments of Puerto Rican attendees. During this protest, Puerto Rican citizens were protesting for workers’ rights and an end to the exploitation of Puerto Rican people.

Black immigrants are often left out of conversations regarding black lives and immigrants in the United States.Knowing Spanish has allowed me to connect with Spanish speakers in the language most familiar to them and I find that very important in social justice to stay away from elitism and connect with marginalized people in the way that works best for them. It doesn’t make sense to use large academic terms with marginalized people who do not have the access to resources to learn the definitions of those terms and it’s more productive to speak to people in their first language than the language that is most comfortable to the person in a position of privilege. As a black Spanish speaker, knowing Spanish has also fueled my interest in learning about Afro-Latinx people and anti-blackness within the Latinx community. Although I’m not Afro-Latinx, I care about the liberation of all black people; regardless of where they’re from in the African diaspora.

Being a Congolese immigrant who has never been to the Congo has motivated me to learn as much as possible about my country and my people.In Spain, I knew I was different because I was significantly darker than everyone else. I was the only black girl at school and one of two black students. Moving to the United States allowed me to be around more black people, but I still knew I was different because I was from another country. Kids thought my name was funny and I was ashamed when my parents spoke French to me in public or my mom wore traditional Congolese clothing outside of our home. More than anything, I wanted to assimilate. In Spain, I didn’t fit in because I was black. But, being in a place with more black people made me think that through assimilation I could “pass” as a Black American. The more time I have spent dismantling my internalized anti-blackness, the more I’ve been able to realize that the goal is not to liberate black people who are just like me, but black people as a whole. If some of us aren’t free, none of us are. I’ve attended Black Lives Matter protests and rallies, spoken at a rally, and I created a campaign against racism at my former university. I have noticed that most of the information that exists on immigrants in the U.S. focuses on non-black immigrants and more specifically, non-black Latinx immigrants. Black immigrants are often left out of conversations regarding black lives and immigrants in the United States. I am grateful for organizations created for and by black immigrants like the Black Alliance for Just Immigration and the UndocuBlack Network. To me, such organizations say, “I see you. I value you.” Being a Congolese immigrant who has never been to the Congo has motivated me to learn as much as possible about my country and my people. A lot of people don’t know about the Congo so when educating others, I use topics they already know about. If someone believes that Black lives matter, they should also care about the Congo as Congolese people are black. If someone cares about fighting sexual violence, they should care about the Congo because there, rape is used as a weapon of war. This is just one way that I have been able to make different parts of me come together.

I’m passionate about many issues, but especially those affecting black women, immigrants, and Congolese people. Not all of the issues intertwine, but many do and the links between different social justice issues are quite similar to the links between my identities. Through social justice and activism, I have found that there’s no place like home for me because home is not a place, but a feeling.

There will probably never be a space specifically for Spanish-born Congolese women living in the United States and I’ve come to terms with that. Marginalized people have many different identities and although we may never find spaces that include every aspect of us, we can use our voices and skills to make spaces as inclusive as possible and in turn, be heard. As long as I find spaces where I feel like my identity is valued and welcomed, I know I’ll be able to continue to work to dismantle the oppressive structures that exist to hurt marginalized people.

I’m passionate about many issues, but especially those affecting black women, immigrants, and Congolese people. Not all of the issues intertwine, but many do and the links between different social justice issues are quite similar to the links between my identities. Through social justice and activism, I have found that there’s no place like home for me because home is not a place, but a feeling.

There will probably never be a space specifically for Spanish-born Congolese women living in the United States and I’ve come to terms with that. Marginalized people have many different identities and although we may never find spaces that include every aspect of us, we can use our voices and skills to make spaces as inclusive as possible and in turn, be heard. As long as I find spaces where I feel like my identity is valued and welcomed, I know I’ll be able to continue to work to dismantle the oppressive structures that exist to hurt marginalized people.