WORDS: JAMILA REDDY | ART: LOVEIS WISE

My partner is genderqueer. I wrote and rewrote this sentence a dozen times, trying to land on something that didn’t feel like a confession.

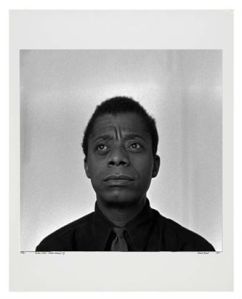

The fact that my partner is genderqueer should not be noteworthy, but it is. It’s important for me to clarify that the gender identity of my partner (who uses they/them pronouns) is not particularly noteworthy to me; I am made aware of how anomalous it is because of how often other people make it so. People’s reactions to my partner — and, when we are together, to us — make one thing very clear: People are utterly confused about gender. Being openly (read: visibly/aesthetically/recognizably) queer is like having a superpower. Without exchanging a single word, I can recognize people’s deepest darkest fears. I know their insecurities. I can see their trauma, their shame, their anger, their desire, their fear. The ability to see people in this way is both terrifying and empowering. Some days, this knowing feels like magic. Some days, it feels like a heavy thing I want to put down. Whenever I am out in public with my partner, who identifies as both trans and genderqueer, I can feel people’s eyes on us from every corner of every room. When I visit my partner in Flatbush, a predominately African American and West Indian neighborhood in Brooklyn, everyday tasks turn into emotionally burdensome endeavors. People — most often (presumably) cis, straight, Black men — stare unapologetically. They survey my partner’s body, their eyes trailing slowly up and down. I have seen people respond to my partner with confusion, disgust, interest, jealousy. I have seen how my partner’s outward appearance causes them discomfort, and I have been compelled to ask why. In the namesake scene of I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin firmly declares, “What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I'm not a nigger...I'm a man, but if you think I'm a nigger, it means you need it… If I'm not a nigger and you invented him — you, the white people, invented him — then you've got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it's able to ask that question.”

This scene stayed with me months after seeing the film because it questions the creation of the white imagination — the cultural psyche that created “the nigger” in the first place. Baldwin appeals directly to white America, asking, “Why did you need the nigger?” You’ve got to find out why.

These words resonate when I reflect upon the varied reasons that homophobia and transphobia run so rampant all over the globe. Through witnessing the way people respond to my beloved, I can only deduce that my partner’s gender nonconformity disrupts people’s understanding of gender roles as a fixed, unchangeable thing. It forces them to question whether gender is, in fact, “nature.” It challenges them to investigate their own adherence to gender — to question their acceptance of the roles they were assigned before they even emerged from the womb.

People attach themselves to rigid boundaries of gender because there is a great benefit involved in doing so. White supremacy created the “nigger” because the myth that Black people were less than human made it easy to justify their oppression. The full humanity of people who don’t conform to gender is similarly distorted, allowing cis people to claim full access to the privileges of “normalcy.”

In the namesake scene of I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin firmly declares, “What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I'm not a nigger...I'm a man, but if you think I'm a nigger, it means you need it… If I'm not a nigger and you invented him — you, the white people, invented him — then you've got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it's able to ask that question.”

This scene stayed with me months after seeing the film because it questions the creation of the white imagination — the cultural psyche that created “the nigger” in the first place. Baldwin appeals directly to white America, asking, “Why did you need the nigger?” You’ve got to find out why.

These words resonate when I reflect upon the varied reasons that homophobia and transphobia run so rampant all over the globe. Through witnessing the way people respond to my beloved, I can only deduce that my partner’s gender nonconformity disrupts people’s understanding of gender roles as a fixed, unchangeable thing. It forces them to question whether gender is, in fact, “nature.” It challenges them to investigate their own adherence to gender — to question their acceptance of the roles they were assigned before they even emerged from the womb.

People attach themselves to rigid boundaries of gender because there is a great benefit involved in doing so. White supremacy created the “nigger” because the myth that Black people were less than human made it easy to justify their oppression. The full humanity of people who don’t conform to gender is similarly distorted, allowing cis people to claim full access to the privileges of “normalcy.”

I don’t want to “normalize” our relationship. “Normal” is too often coded language for white, too often means “just like the rest.”Though it sparks a quiet rage within me that my partner cannot move through the world without being hyper-surveilled, I cannot blame the general public for their ignorance and fear. Trans erasure is a global epidemic. Other than a few celebrity names — Caitlyn Jenner, Laverne Cox, RuPaul — gender non-conforming folks rarely appear in movies, on TV, in magazines. Although Western media is slowly making progress towards more trans visibility, people who do not conform to gender are still too often pushed to the margins of the cultural imaginary. When they’re not erased, they’re sensationalized — larger than life, always performing — characters. No one ever sees RuPaul with her make-up off, at the grocery store. We don’t see Laverne cranky on her way to therapy or shopping for chickpeas as the SuperFood. It’s no wonder people stare at my partner. Trans folks are supposed to be glitzed and glammed up on a stage somewhere, not riding beside you doing homework on the A train. Why? Why is it necessary for people to believe we don’t exist? Why do people feel the need to constantly distance themselves from queerness? From gender fluidity? I can only deduce that gender nonconforming people living in our truth are their clearest mirror, and they don’t like what they see. The cultural fear of gender nonconformity puts trans people at a very serious risk. I constantly have to dispel my worry about my partner walking alone in New York — about them being the next victim of some senseless, hate-filled crime. There is too much evidence that being read as trans/queer/gender non-conforming/nonbinary has violent and lethal consequences. People all across the globe are being imprisoned, attacked, and even murdered for not adhering to the social expectations attached to gender. In Chechnya (a federal republic of Russia), over a hundred men suspected of being gay have been abducted, tortured and some even killed, as part of a coordinated government campaign” to “purge” society. In Uganda, where it is illegal to be gay, people live secret lives to protect themselves from assault, imprisonment, and death. In the United States, 21 trans people have been murdered this year alone. Being outwardly queer — which, in partnership, means being outwardly affectionate towards and visibly connected to my trans partner — is, in and of itself, an act of resistance. I push back on the myth that we don’t exist; I uplift the truth simply by existing in the world. I don’t want to “normalize” our relationship. “Normal” is too often coded language for white, too often means “just like the rest.” I want to live to see a day when queer and trans love is a part of the cultural vocabulary. I want to be able to walk through the park with my love without feeling like I’m in a two-person parade. I want people to know that all kinds of love are possible, and to do themselves the service of questioning gender for themselves.

Being gender non-conforming is to live with daily reminders of all the ways human beings are spiritually, emotionally, and psychologically enslaved by social constructs.Though I may not always “feel” cis, I sure as hell benefit from cis privilege. Unless my partner is by my side, I am most often not read as queer, and I know this allows me to move through the world with a greater degree of safety. Being in this relationship has allowed my own limited (and privileged) understanding and expression of gender to loosen and evolve. I am still unpacking my own identity and my own relationship to gender. Loving someone who is trans has allowed me to reflect upon my own complicity in upholding the gender binary and to give myself permission to question the constructs that don’t serve me, that to let go of the ones that don’t feel authentically mine. To exist beyond the limits of gender is liberating in so many ways. Being in a relationship that doesn’t conform to gender allows us to truly be creative about our partnership. It allows us to imagine the widest range of possibilities for our lives together — to think outside of the narrow confines of what we “should” be doing, according to the patriarchy. Being gender non-conforming is to live with daily reminders of all the ways human beings are spiritually, emotionally, and psychologically enslaved by social constructs. So many people base their lives on what they are told they should be doing instead of what they want to do. They deny themselves opportunities for love, intimacy, deep and profound connection. Let me be clear: Loving a trans person does not make me special. It does not make me a hero. Loving my trans partner is not difficult, and being in a relationship with a trans person does not make my life hard. What is difficult is constantly navigating violent heteropatriarchy — is having to fight every single day to show up in the world authentically without consequence, and without shame. Despite how the world responds, I know that there is nothing remarkable about us. I know that we are human and that our love is revolutionary simply because we’ve given ourselves permission to experience it. What is remarkable is the fact that we are still alive. We are walking, breathing evidence of what is possible. We are living proof.