The Fast and the Furious

WORDS: WALLACE MACK | ART: FAYE ORLOVE

To live in South Carolina during the month of November is to live in a constant state of ambiguity.

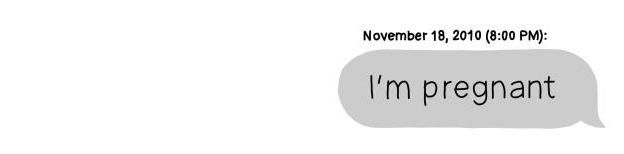

In November, it’s not quite as hot as it used to be, but it’s nowhere near cold on most days. Students are still posted up in the parking lot well after school, blasting music from Toyota Camrys and big body SS Impalas and 2007 Honda Accords. Our principal warns us in the mornings that once school is out, we are to leave campus immediately— zero loitering will be tolerated. She was careful to let her female students know that “decent girls don’t hang around, swinging and swaying in-between car doors after-school.” I always imagined asking her, in a fictitious moment of teenage rebellion, if that meant decent girls rode the bus, but I knew that wasn’t true either. It couldn’t be true with all the finger-popping we used to do on the back of those cheese wagons. Some of these cars are headed for basketball practice. Some of these cars will pull into the local rec center where the drivers will hotbox a blunt, or maybe two. For boys growing up in the south, our secrets belong to our cars. That is precisely the reason why we spend so much time fixing them up. We tint the windows so that our secrets can ride around with us in peace. We post up at the local car wash to ensure that our secrets feel clean, even though most of them are covered in filth, and to tell the truth, clean cars ride better. “Aye, lemme get some of your Armour All real quick!” My dad always told me that you can tell a lot about a man with a dirty car. Rims are necessary because pretty secrets should match that pretty smile you flex when you’re driving slow, windows down and grill exposed, “What y’all getting into after this?” I need my car to be fast because I can’t have your secrets beating mine on the road, now can I? We drape black ice air fresheners on our rear-view mirrors because most of our secrets are lies, and who can bear the scent of a lie?I was 16 when this girl I was really digging told me that she was expecting.Some of these cars will travel about a mile down the road to this spot we used to frequent called Craver’s Corner. Back then, you could get a 6 piece wing and fries for like $5 and drown the whole tray in hot sauce and ranch dressing. Some of these cars won’t leave the parking lot because some of these cars won’t crank— we affectionately refer to their owners as broke boyz. Safe sex will happen in a few of these cars, but for the rest of them, well, we call that raw-dogging, and raw-dogging is not a secret. We are the fast and the furious. To live in South Carolina during the month of November is to live in a constant state of ambiguity. You can’t really tell if there’s love in the air, but there is a slight chill on Friday nights. It’s the kind of chill that’s cold enough for bored kids to seek the heat of familiar bodies, but just warm enough that you only need a hoodie, gym shorts and Nike slides to catch one. What’s in the air might not be love, but what we feel for certain is that slight chill and a whole lot of teenage lust. Parked cars with active engines and foggy windows are, more often than not, way warmer than they should be. I was 16 when this girl I was really digging told me that she was expecting. It was the result of my first time; a few awkward thrusts in what is now an abandoned Wal-Mart parking lot. It was bad— kind of quiet, mostly cramped and very stiff, but it was my first time. About a month later, she texted me and told me that, in that really bad 10 or so minutes of sex, I had potentially knighted myself a father, and I was excited.

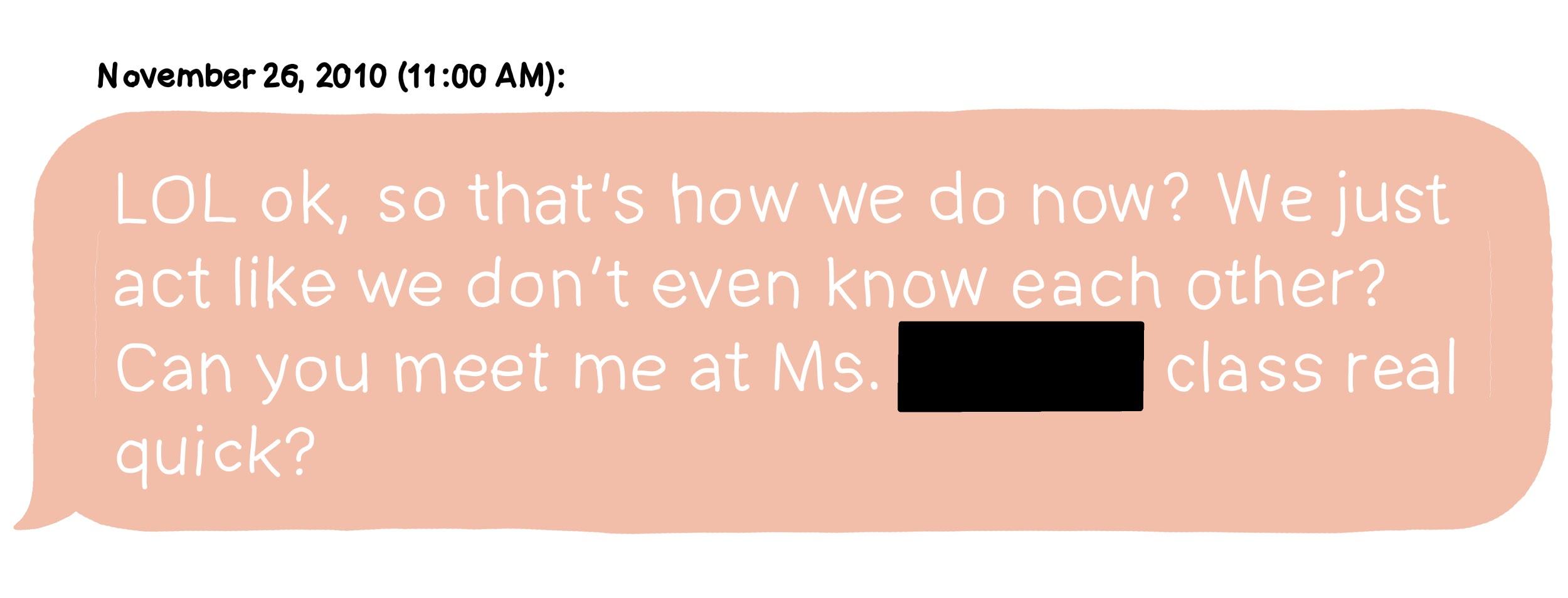

The excitement was short-lived. A few days later she called things off and disappeared. I was not surprised, but understanding and acceptance are not always one and the same. She was older than me and much more alive. My naivety allowed me to believe that I could drop out of school and bag groceries full time to raise a child. I’m sure my naivety reminded her that I'd be raising one child, she'd be raising two.

“I know you heard she got an abortion?”

I heard it in the hallways that January, two whole months since I’d last spoken to her. I can’t say that I was angry, but I can say that I was sad and I was embarrassed. There’s a peculiarity to being 16 years old and thinking you know everything about life. For months I carried that pain around like bricks in my Jansport backpack. On the weekend, I’d leave that backpack in my car. I learned what depression was for the first time. I isolated myself from family and friends. I lived in darkness. While I was afforded the privilege of shrinking into myself, her life was put on full display. I started to be more intentional about locking my car doors because apparently, my secrets were getting out.

“Did she really?”

“I heard she went to Atlanta to get it done.”

The details of her life became expensive garments that an entire school suddenly became interested in fondling and trying on. The embarrassment that I felt was heavier than losing a high school girlfriend, and believe it or not, bigger than the idea of losing a shot at fatherhood. Her secrets or rather, our secrets, were being window shopped. I was embarrassed that she decided to go through it alone.

The excitement was short-lived. A few days later she called things off and disappeared. I was not surprised, but understanding and acceptance are not always one and the same. She was older than me and much more alive. My naivety allowed me to believe that I could drop out of school and bag groceries full time to raise a child. I’m sure my naivety reminded her that I'd be raising one child, she'd be raising two.

“I know you heard she got an abortion?”

I heard it in the hallways that January, two whole months since I’d last spoken to her. I can’t say that I was angry, but I can say that I was sad and I was embarrassed. There’s a peculiarity to being 16 years old and thinking you know everything about life. For months I carried that pain around like bricks in my Jansport backpack. On the weekend, I’d leave that backpack in my car. I learned what depression was for the first time. I isolated myself from family and friends. I lived in darkness. While I was afforded the privilege of shrinking into myself, her life was put on full display. I started to be more intentional about locking my car doors because apparently, my secrets were getting out.

“Did she really?”

“I heard she went to Atlanta to get it done.”

The details of her life became expensive garments that an entire school suddenly became interested in fondling and trying on. The embarrassment that I felt was heavier than losing a high school girlfriend, and believe it or not, bigger than the idea of losing a shot at fatherhood. Her secrets or rather, our secrets, were being window shopped. I was embarrassed that she decided to go through it alone.

I imagined her sitting in some shitty doctor’s office, cold and scared. I remembered what it was like to be scared. On the night that we first had sex, I was terrified. But one broken curfew and two bruised knees later, I looked back at the window from which I’d jumped and found my thrill. I remembered what it was like to be scared, but I was never cold, at least not with her. And after all of those thrills, after that thrill specifically, somehow those bruised but agile knees weren’t attached to legs that could run fast enough to be by her side. She didn’t let me be by her side.

Six years later, I’ve traded my car for the pedestrian existence of a New Yorker. I have fewer secrets these days and no need for such a large space to store them. It is in New York that I have learned to transport my remaining secrets in Ubers and taxis. The subway functions as a peculiar shared space of which, I will never feel comfort in storing anything, particularly not my secrets. I opt for headphones and books for the commute instead. This is where I was able to explore The Mothers by Brit Bennett. I read each page blindly, wandering aimlessly from chapter to chapter until I finally sealed the book shut. The Mothers is more than a coming-of-age tale about a girl named Nadia Turner growing up in Southern California and navigating life after abortion, it’s also a painful reminder of the ways that men fail to show up for black women. Through intricate storytelling and robust character development, Bennett explores topics like the hypocritic nature of the church, suicide, mental health, and abortion, reconciling them with the idea of community. In The Mothers, readers learn how it is completely possible to belong to a community and still not at all (truly) belong.

The novel’s plot is driven by a relationship between Nadia Turner and Luke Sheppard, a boy who captivates her in a way she’d never experienced. As the son of a preacher, Luke represents a forbidden temptation in Nadia’s life. While loving, Luke and Nadia’s relationship is plagued by secrecy and destroyed when Luke learns that Nadia is pregnant. As the son of a preacher, Luke opts to ghost on their relationship, an effort that helps him save face and protects his family’s reputation. Nadia sits cold and scared, in some shitty doctor’s office for an abortion procedure, and “when it was over, Luke never came for her.” Given the opportunity to be there for someone he claimed to love, he chooses not to. Maybe his car wouldn’t crank. Isn’t it amazing how sometimes, our cars seem to have a mind of their own?

I imagined her sitting in some shitty doctor’s office, cold and scared. I remembered what it was like to be scared. On the night that we first had sex, I was terrified. But one broken curfew and two bruised knees later, I looked back at the window from which I’d jumped and found my thrill. I remembered what it was like to be scared, but I was never cold, at least not with her. And after all of those thrills, after that thrill specifically, somehow those bruised but agile knees weren’t attached to legs that could run fast enough to be by her side. She didn’t let me be by her side.

Six years later, I’ve traded my car for the pedestrian existence of a New Yorker. I have fewer secrets these days and no need for such a large space to store them. It is in New York that I have learned to transport my remaining secrets in Ubers and taxis. The subway functions as a peculiar shared space of which, I will never feel comfort in storing anything, particularly not my secrets. I opt for headphones and books for the commute instead. This is where I was able to explore The Mothers by Brit Bennett. I read each page blindly, wandering aimlessly from chapter to chapter until I finally sealed the book shut. The Mothers is more than a coming-of-age tale about a girl named Nadia Turner growing up in Southern California and navigating life after abortion, it’s also a painful reminder of the ways that men fail to show up for black women. Through intricate storytelling and robust character development, Bennett explores topics like the hypocritic nature of the church, suicide, mental health, and abortion, reconciling them with the idea of community. In The Mothers, readers learn how it is completely possible to belong to a community and still not at all (truly) belong.

The novel’s plot is driven by a relationship between Nadia Turner and Luke Sheppard, a boy who captivates her in a way she’d never experienced. As the son of a preacher, Luke represents a forbidden temptation in Nadia’s life. While loving, Luke and Nadia’s relationship is plagued by secrecy and destroyed when Luke learns that Nadia is pregnant. As the son of a preacher, Luke opts to ghost on their relationship, an effort that helps him save face and protects his family’s reputation. Nadia sits cold and scared, in some shitty doctor’s office for an abortion procedure, and “when it was over, Luke never came for her.” Given the opportunity to be there for someone he claimed to love, he chooses not to. Maybe his car wouldn’t crank. Isn’t it amazing how sometimes, our cars seem to have a mind of their own?

I think often about being cold and scared. I imagine standing over a toilet seat, reading from a flimsy white stick covered in pee that reads “pregnant.” I imagine trying to scrape together a few hundred dollars to bury a secret that has no hope of remaining a secret. All of my secrets belong to my car, and no one is attempting to take my car because no one knows that my car holds secrets. I doubt that anyone cares that my car holds secrets. I think a lot about weight and burden. I walk up and down the halls of my memory and see fingers pointing and people whispering. I see a future for myself some days and some days I see none at all. I am paralyzed with fear. I do not speak up. I watch. She carries. This was never my burden to bear and it could have never been my call to make. For all of the boys with cars, It is never our call to make. As Nadia lies cold and scared on the doctor’s table, she thinks to herself, “Suffering pain is what made you a woman. Most of the milestones in a woman’s life were accompanied by pain, like her first time having sex or birthing a child. For men, it was all orgasms and champagne.”

I think often about being cold and scared. I imagine standing over a toilet seat, reading from a flimsy white stick covered in pee that reads “pregnant.” I imagine trying to scrape together a few hundred dollars to bury a secret that has no hope of remaining a secret. All of my secrets belong to my car, and no one is attempting to take my car because no one knows that my car holds secrets. I doubt that anyone cares that my car holds secrets. I think a lot about weight and burden. I walk up and down the halls of my memory and see fingers pointing and people whispering. I see a future for myself some days and some days I see none at all. I am paralyzed with fear. I do not speak up. I watch. She carries. This was never my burden to bear and it could have never been my call to make. For all of the boys with cars, It is never our call to make. As Nadia lies cold and scared on the doctor’s table, she thinks to herself, “Suffering pain is what made you a woman. Most of the milestones in a woman’s life were accompanied by pain, like her first time having sex or birthing a child. For men, it was all orgasms and champagne.”

The novel explores themes of guilt and rejection, and as Reni Eddo-Lodge writes, “What is expected of women’s bodies, and what happens when black women do not perform as they should.” Nadia’s existence as a fictional character is a testament to the racist, patriarchal double standards that ensure that black girls are not just more harshly disciplined in white supremacist schools, but also more harshly judged when they get home. This is not the plight of boys with cars. Luke lives a life free from public ridicule and invasion of privacy, while Nadia learns to live a life under the microscope of her hometown. My reputation at the time went mainly unscathed. People buzzed around about potential baby daddies, but I suffered no serious consequences. Losing no social capital, I was celebrated in many circles as one of the first of my peers to lose their virginity. I had a car and it was shiny and new. My car had a sunroof too and boy, you should have heard that system!

The evil of patriarchy is that it functions as a many-headed hydra. The double standard around pregnancy and the stigma surrounding abortion are not disconnected issues, they are just two heads of the hydra. In The Mothers, we learn that our double standards do not protect men either, as Luke grows from an emotionally stunted boy, to a frustrated and angry man with wanna-be daddy issues. Cars with secrets need good insurance, ask me how I know.

The novel explores themes of guilt and rejection, and as Reni Eddo-Lodge writes, “What is expected of women’s bodies, and what happens when black women do not perform as they should.” Nadia’s existence as a fictional character is a testament to the racist, patriarchal double standards that ensure that black girls are not just more harshly disciplined in white supremacist schools, but also more harshly judged when they get home. This is not the plight of boys with cars. Luke lives a life free from public ridicule and invasion of privacy, while Nadia learns to live a life under the microscope of her hometown. My reputation at the time went mainly unscathed. People buzzed around about potential baby daddies, but I suffered no serious consequences. Losing no social capital, I was celebrated in many circles as one of the first of my peers to lose their virginity. I had a car and it was shiny and new. My car had a sunroof too and boy, you should have heard that system!

The evil of patriarchy is that it functions as a many-headed hydra. The double standard around pregnancy and the stigma surrounding abortion are not disconnected issues, they are just two heads of the hydra. In The Mothers, we learn that our double standards do not protect men either, as Luke grows from an emotionally stunted boy, to a frustrated and angry man with wanna-be daddy issues. Cars with secrets need good insurance, ask me how I know.

It’s now May 2017 and in Harlem, the sun is beginning to peek from behind the clouds. I do not know what it means to grow up as a teen in Harlem, but I know that the vast majority of them do not have cars. Cars here become stoops and street corners and empty trains on Sunday nights. I do not imagine that the boys here bury their secrets in cars. It’s now May 2017 and the streets are beginning to hustle and bustle with activity. Boomboxes and Nike slides are back. Cookouts and cracked fire hydrants are back too. I will enjoy this summer in ways that many women will not. Conversations about “what decent girls wear” are back. Catcalling is back. I read recently that evening curfew for black girls in D.C. might be back soon too. These are also a part of the many-headed hydra we call patriarchy. They function closely with the guilt, shame, and rejection that many women experience within their own communities. Women have cars too, but rarely are they afforded the privilege of storing their things untouched.

This summer, boys will stand on street corners Friday through Saturday, knowingly and unknowingly harassing women. When confronted, they will cite what the women choose to wear as an excuse. These boys will be pardoned by the “nature of being boys”. Luke and I may not be those boys standing on the corner, but those boys will be our friends. On Sunday Morning, Nadia Turner and these same women will be harassed again, this time from the pulpit of their grandmother’s church, told by the pastor that they should “dress how they want to be addressed.” The violent nature of patriarchy will extend beyond the pulpit and into scowling faces of church mothers who will turn their necks menacingly from the front row to glare at the “fast-tailed girls” in the congregation. Luke and I will sit in the back of the church completely unnoticed and afterward we will journey home in our cars.

It’s now May 2017 and in Harlem, the sun is beginning to peek from behind the clouds. I do not know what it means to grow up as a teen in Harlem, but I know that the vast majority of them do not have cars. Cars here become stoops and street corners and empty trains on Sunday nights. I do not imagine that the boys here bury their secrets in cars. It’s now May 2017 and the streets are beginning to hustle and bustle with activity. Boomboxes and Nike slides are back. Cookouts and cracked fire hydrants are back too. I will enjoy this summer in ways that many women will not. Conversations about “what decent girls wear” are back. Catcalling is back. I read recently that evening curfew for black girls in D.C. might be back soon too. These are also a part of the many-headed hydra we call patriarchy. They function closely with the guilt, shame, and rejection that many women experience within their own communities. Women have cars too, but rarely are they afforded the privilege of storing their things untouched.

This summer, boys will stand on street corners Friday through Saturday, knowingly and unknowingly harassing women. When confronted, they will cite what the women choose to wear as an excuse. These boys will be pardoned by the “nature of being boys”. Luke and I may not be those boys standing on the corner, but those boys will be our friends. On Sunday Morning, Nadia Turner and these same women will be harassed again, this time from the pulpit of their grandmother’s church, told by the pastor that they should “dress how they want to be addressed.” The violent nature of patriarchy will extend beyond the pulpit and into scowling faces of church mothers who will turn their necks menacingly from the front row to glare at the “fast-tailed girls” in the congregation. Luke and I will sit in the back of the church completely unnoticed and afterward we will journey home in our cars.

Much of love is the result of listening.In order to do the work of supporting women, we must realize that the one true thing that keeps our double standards alive is our unwillingness to hold ourselves accountable. Much of the work we must activate in dismantling patriarchy will involve us doing something that we’ve always claimed to do, but have never actually done: listening to women. No longer can we silence black girls and feign shock when they run away from home. We have to open the lines of communication with them. We have to take more seriously their claims of sexual assault. We have to create safe spaces for women to talk about sex. We have to critically engage with their art, because often times, the answers are right there. We have to kill the stigma behind pregnancy and abortion. The saying “boys will be boys” has long permeated our culture. It’s a living, breathing social ill that will continue to claim casualties in our communities. The more we feed it, the bigger and badder it will get. Men often speak about what it means to love black women and what protection looks like. Much of love is the result of listening. The Mothers is an introspective meditation that ultimately asks us if we actually hear black girls. If we hear black girls, are we listening? “Boys will be boys” loses its validity when you consider that one day, “boys” trade toys for cars. For boys growing up in the south, our secrets belong to our cars. That is precisely the reason why we spend so much time fixing them up.